Why I Climb – Reflections on a month at Arapiles (by Ryan)

I FEEL LIKE

I CAN

BE MYSELF

UNJUDGED

AND UNBOUND

BY SOCIETY

Why on God’s green Earth do you guys climb mountains?

Because we’re insane. Can’t be any other reason.

This iconic answer was given to a disbelieving media by the enigmatic Warren Harding upon completing the now-legendary first ascent in 1970 of the Dawn Wall on Yosemite Valley’s ‘El Capitan’ cliff – very possibly the most recognised, dreamt about and attempted piece of rock in the entire world.

No one took the answer seriously at the time – rather it was dismissed as the utterings of an alcoholic thrill seeker who’d just summited a nine hundred metre high cliff – but in actuality Harding might have been more correct than anyone gave him credence for.

The beauty of climbing is that it can’t be quantified. There is no justifiable reason for pitting one’s body against an inanimate object. And yet in the modern era – over fifty years since Harding’s ascent – rock climbing is amongst the fastest growing sports in the world.

Why is that?

Ask five climbers why they do what they do, and more than likely you will receive five different answers. Ask ten. Ask fifty. Ask a hundred – all equally as vague and non-committal as the last. In fact, if you were to categorise all these answers, highly likely the most common one would be along the lines of “I don’t know.”

Heck, for a long, long time I didn’t really know either. I’ve been climbing for over eleven years now – nearly half my life – having started out as a naïve, scrawny little thirteen year old whose high-school had a small top-rope gym used by the outdoor education classes. I don’t really remember what exactly drew me to it initially – maybe it was because I’d recently fallen out of enjoying other sports I’d grown up playing and I enjoyed the individuality of climbing. Maybe it was because my friends also enjoyed it. Maybe it was because of my childhood spent living in national parks, climbing every tree and boulder I could.

Either way I enjoyed it and was good at it, so I stuck with it – though I never really pondered the question of why.

As I grew and developed my skills and discovered a whole world beyond that little top-rope gym – a world of outdoor cliffs and trad gear, of other gyms and competitions – so too did my motivations for climbing.

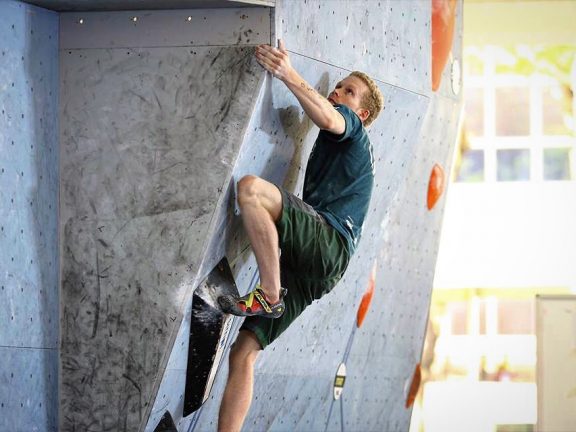

I think a big point of difference in why people climb is to do with what lured them to the sport to begin with. To a lot of people – especially these days with how accessible bouldering in particular is – climbing is along the lines of an interest, a hobby, a pastime; something to do with friends on the weekend or if time allows, after work. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with that at all, let me be clear right now. People’s reasons for climbing are their own and who am I – or anyone else – to judge them for that. For me though, climbing is my life, my world. I live it, I breathe it, I need it to function. Through the ups and downs of life, through some fantastic times of joy, unforgettable trips and lifelong friends and equally through some truly dark and depressing times, climbing has been the one constant in my life, the one thing that I can fall back on – like a warm embrace from a friend – and rediscover myself.

Amongst the hormonal struggle of high school – of fitting in and being cool and being recognised – I found comfort and identity in the world of competitive climbing. Arrogant little teenage me revelled in training, breaking chin-up records and winning competitions. My reason for climbing back then solely centred on finally having an activity that I could be – and was – the best at. After graduating school and winning junior state titles, making open finals and competing internationally, that perspective soured and shifted once – after coming agonisingly close to representing Australia at the 2016 World Youth Climbing Championships – I discovered how fickle, biased and unforgiving the world of competition climbing can be. In the following years, I drifted away from that side of the sport after realising the toxic personality traits it had given me, and returned instead to my Central Australian roots and focussed on climbing outdoors in what was a merciful and much needed escape from the rest of the world.

I found that escape at Mount Arapiles.

Known as Dyurrite to the indigenous Wotjobaluk people, this mound of quartzite sandstone rising out of western Victoria’s vast Wimmera plains was once an island in an ancient inland sea. These days it is Australia’s premier trad climbing destination – of worldwide renown.

I first came here on a school trip in 2014, and was completely blown away by the quality of the rock and the climbing – a vast change from the crumbly cliffs of Central Australia – and I have returned every year since.

While climbing has been the centre of my life, so too has Arapiles been the centre of my climbing.

It is a place I’ve always felt at home. The rest of the world doesn’t exist out here. Angry horns and shouts of city traffic are replaced by a chorus of Kookaburras, Magpies and Rosellas. Concrete pavement by open shrubland on which Kangaroo’s graze peacefully. And hurried people all demanding different things from you – trying to get you to open up, or change to something you know you aren’t – is replaced by a tight-knit and wondrous little community of like-minded souls from all walks of life. Different cultures, different backgrounds, different personalities all camping together, climbing together, laughing together, unified and connected by this magical little cliff in the middle of nowhere.

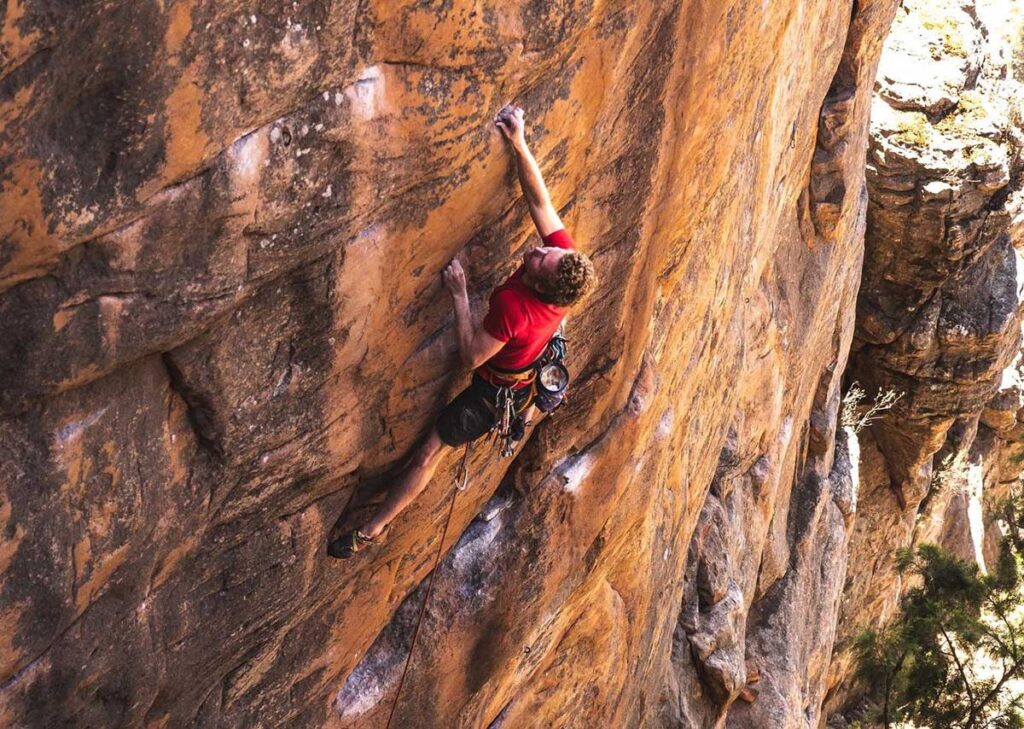

At Arapiles, I feel like I can be myself, unjudged and unbound by the rest of society. Onsighting classic trad routes on glorious orange rock, projecting hard in the dark and dingy gullies in between. Diving in supermarket dumpsters for a free meal to be shared back at camp, free soloing easy multi pitches at night, guided by unblemished moonlight. I don’t feel lost out here, I feel free

But again, I never really comprehend why.

Until this most recent trip.

I had a month at the Mount, and just like my previous trip to Tasmania, I was on my own with no real plan. I just wanted to escape the city and get back into enjoying climbing after a tough few months off with a major finger injury.

I was drawn to a route called ‘Final Departure’ – a vaunted grade 27 sport climb high up on the proudest part of the mount, overlooking the entire campground. It’s long, sustained, and very hard for the grade.

I had no plans to attempt the climb initially – climbing of that grade wasn’t something I was even considering after being injured for so long – but some friends of mine were projecting it and I jokingly decided to give it a go.

Much to my surprise, the majority of the moves came together quite easily, and on my third session I’d solved the crux sequence high in the route – a sustained and very intricate sequence of bad side-pulls and lots of small, technical foot moves – but knew that to link it all together would still take a lot of work.

I decided to take some rest and two days later awoke to an avian dawn chorus very early in the morning. I decided to solo up an easy buttress and greet the sunrise at the top of the cliff with some stretches and some yoga in preparation to climb hard later in the day.

I looked across the valley just as the first rays of sunlight kissed the route – quickdraws glinting alluringly in the light. I closed my eyes and visualised the moves I needed to do. A strange self-confidence came over me – something that I’ve always struggled with throughout my entire climbing career – and I opened my eyes, focussed on the chalk of the crux holds and whispered to myself:

“This is going down today”

A few hours later I was at the base of the climb, tied in and ready to go. I had warmed up and was feeling good. The cliff was shaded and the wind was still. Everything was perfect.

I actually climbed pretty badly through the first half of the route. Whether it was nerves or using freshly re-soled shoes, I don’t know. In the rest before the crux I was shaky, breathing heavily with anticipation. Even the crux itself was less than ideal. I didn’t stick the initial holds well, misplaced some feet and barely stuck a crucial left hand crimp.

But once I stuck that hold, everything changed.

All that confidence, all that assurance and belief I’d felt that morning came rushing back, and all doubt was purged completely from my mind. It’s hard to describe, I just knew I could do the rest of the moves.

And I did.

The remaining sequences were executed perfectly. Feet stayed on, hands didn’t open, the rope kept moving through the belay device.

Upon clipping the chains at the top, there was no outburst of emotion, no glorious cheers of victory, not even an exhale of relief. I just sat there, basking in a feeling I’d never once experienced in all my years of climbing.

In that moment, everything faded. Mind and body become weightless. All the garbage in the world ceased to exist. Bills, deadlines, responsibilities, none of it mattered. All that was left was an entity – myself – existing in this exact point of space and time.

The Greek philosopher Epicurus called it ‘ataraxia’ – a serene state of calmness. But human. Not some all powerful being full of wisdom, void of emotion, perfect and infallible. Human.

And how wonderful to be just that.

Was this the insanity that Harding was referring to? A state of absolute peace from the chaos of the greater world, afforded by nothing other than some humble, insignificant, inanimate piece of rock? I don’t know. I never will, and it is not worth wasting the energy trying to find out.

Now that I have tasted that feeling though, I do not intend to forget it. And in future when people ask me why I climb, that is the answer I will give.